Welcome to the emotional internet

Remember the Jaguar rebrand fiasco?

Yeah, that was only two weeks ago. But it feels like forever ago, right?

I spotted the rebrand late, the Thursday night before the Friday that everyone jumped on it. I was grabbing around for things to write about here, and I made a note to write about it. It is literally perfect for this newsletter: how a legacy car company is going electric, and with completely pivoting its brand. I was confounded and interested. I was excited to write about it. I went to bed.

The next day, I didn’t really check any social accounts until the afternoon and I really couldn’t believe my eyes when I did. The internet had gone absolutely batshit for what Jaguar had done. Takes for days. So. Many. Takes.

Even Mark Ritson, whose column over at Marketing Week I read religiously, had jumped on the topic within a day. Mark’s columns are topical, but rarely about the zeitgeist.

Every single post on LinkedIn was full of vitriol for Jaguar and the decisions they’ve made. It was unbelievable.

So look, today’s post is not about that. Well, it is and it isn’t. We’re not talking about the Jaguar rebrand today, explicitly, because you have heard every possible take about it by now. What I will say is this: I don’t think the Jaguar brand is dead, like so many are forecasting. It cannot happen.

They have a two year window to release a car, in which they’ll either double down on their unhinged brand strategy and find a way to make it work (tweak until it hits), or they’ll – psych! – tell us all it was a big joke and reassure us that they’re going back to the way things were.

Either way, Jaguar is here to stay, and whether they planned this or not is pretty by-the-by now. They have a huuuuge amount of buzz around them and that will, whether this whole thing was intentional or not, be a big advantage for them.

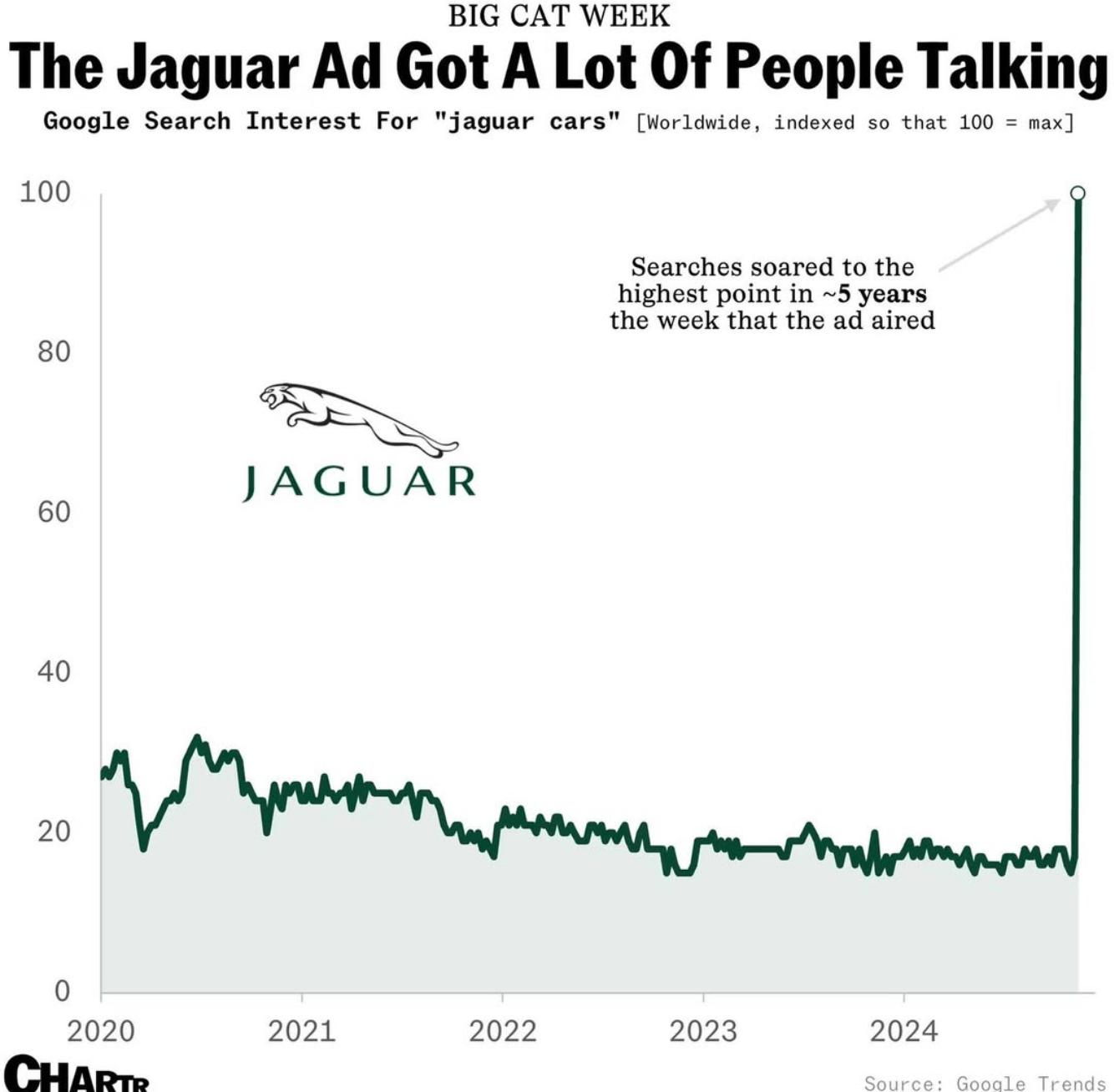

I mean, look at this chart:

So yeah, Jaguar will be fine.

So what are we talking about? Well, it’s got something to this and Bluesky.

A new home on the internet, for some

A few days before Jaguar set the internet alight, something else did.

A tipping point was reached over at X – likely to do with its degrading service for non-right-wingers and catalysed by Trump’s win in the US Presidential Election.

Suddenly, in mere days, there was huge momentum and incredulous enthusiasm for Bluesky, a research-project-turned-American-benefit-corporation spun out of Twitter in 2021.

It felt like, in the space of a couple of days, every single centre-left, liberally-aligned internet optimist had thrown in the towel at X and started professing an unwavering commitment to Bluesky. There were rounds and rounds of praise of how “nice it felt” over there, in comparison to its ever-uglier colleague, the former Twitter.

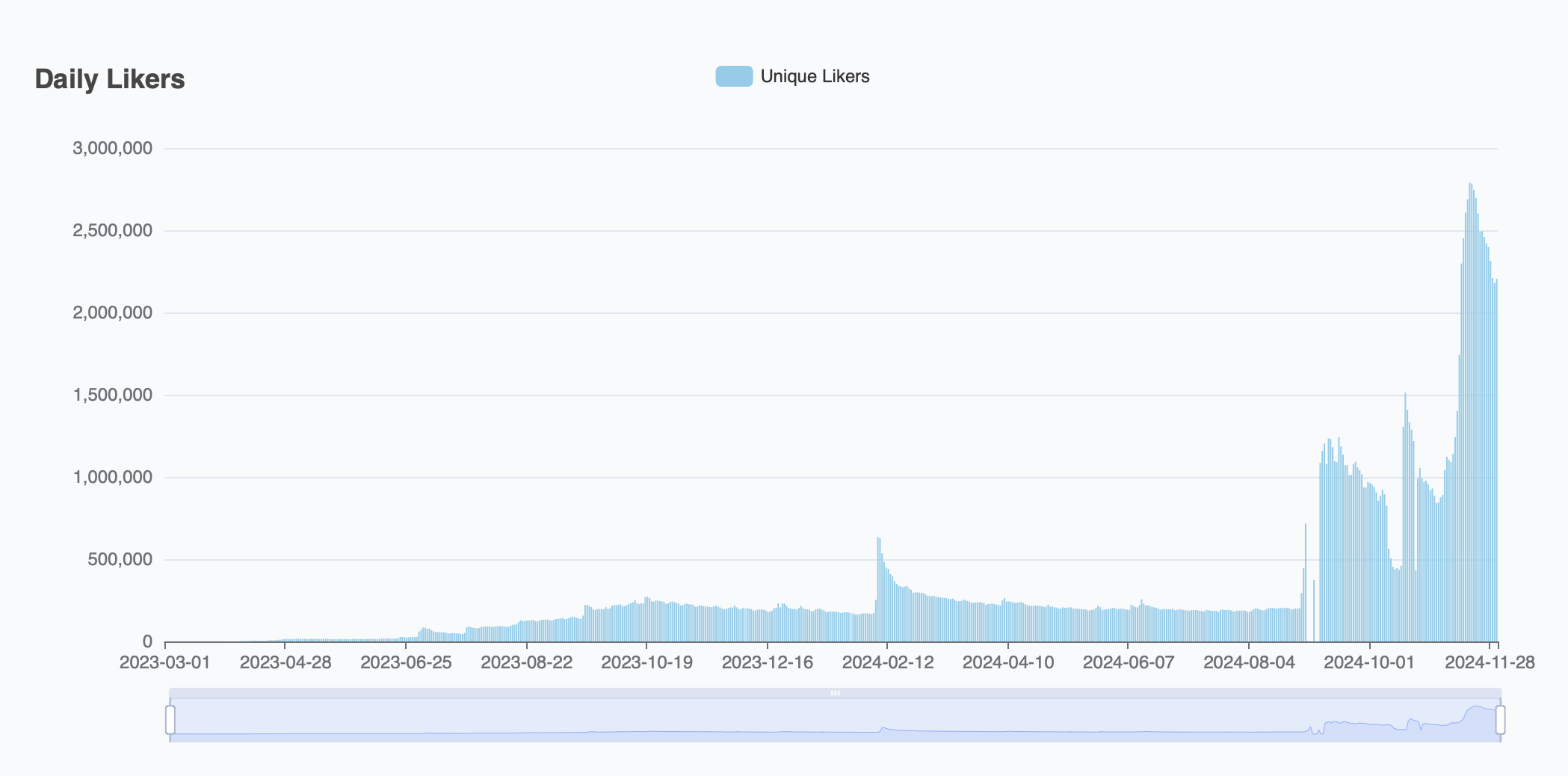

Here’s another chart for you. In the space of 9 days, the number of daily likers, a good proxy for engagement, tripled from 1 million to 3 million:

And the service now boasts 20 million users, after kicking off 2024 with less than a million.

The internet is getting more emotional

I think the last big moment we all got together on the internet like this was in 2022. Looking back, this was a genuinely era-defining moment. It was, of course, for ChatGPT. At the time it was a research preview that went viral without meaning to. ChatGPT is now a big consumer brand in its own right.

In just 5 days, it had a million users. It now gets 600 million visits per month, and has over 180 million registered users (all according to Exploding Topics). This was a moment of pure viral explosion, and set the stage, I think for the AI era we find ourselves living in today.

But here’s the thing that’s different. In 2022, this viral moment was driven by intrigue and interest. A genuinely new tool that unlocked a lot of very cool things. Even people who had studied artificial intelligence for decades were stunned by it. The virality was driven by the fact that this was a technology of the future.

The Jaguar and Bluesky moments feel different. They are different because visceral emotion was the big driver of virality.

Is the monoculture back?

Listen to any entertainment or cultural commentators and they’ll tell you that we used to live in a monoculture, but now that’s gone. We all watched the same telly, listened to the same music, cheered for the same football games.

But since the internet arrived, more choice meant a fracturing, and eventual destruction, of singular cultural moments. Fewer people than ever are watching Saturday night telly. Fewer still are listening to breakfast radio shows.

That’s because you can choose a podcast about your very niche hobby and listen to it on your own schedule. Or you can choose from the Netflix algorithm that has somehow worked out that you love whodunnits set in the seventies. Or… just scroll through hours of portrait videos of cats. People spend their time in more and more distinct ways because the internet gave us abundance.

This means that large groups of people no longer experience culture together. No more monoculture.

Well, I think this take might be true for geographies. The UK does not behave like a singular identity any more. That era is over. The same is true in the US. And Europe and everywhere else.

But I think, if there can be such a thing, there are now multiple monocultures and they all live on the internet. You have liberal Bluesky enthusiasts, right-wing Joe Rogan fans and not-politically-affiliated-Instagram-lifestyle-internet-people. Among many, many more.

The reason I think we can call them monocultures, even if there are a lot of them, is because people in them really all do experience the same world together. They just don’t live geographically in the same place, they live virtually in the same place.

Hanging out on the same platforms, within the same algorithms, saying the same things in slightly different ways.

Many monocultures

Admittedly, this has been the case on the internet for years.

There have always been communities of people that are interested in the same topics. But these people have purposefully gathered around topics of interest to them. People join subreddits about their interests or follow influencers that talk about them. They purposefully seek them out.

But the internet monocultures are different, I think. It’s not a group of enthusiasts talking about their interests. It’s similar cohorts of people experiencing the internet in a similar way, in their algorithmically chosen feeds.

I think this explains a lot of 2024. It explains how Trump won so pervasively without it ever registering on the internet experience of millions of (more liberal) Americans. It explains why Bluesky had an exploding moment amongst those liberals. And it explains why it felt for me like every person on the internet hated the Jaguar rebrand over the last few weeks.

Defining these as moments of monoculture is important to our understanding of them. Because people feel ownership of their own cultures. They want to participate. So when marketers see a brand refresh gone wrong, they can’t help but contribute.

And when liberal-leaning, politically engaged optimists spot other likeminded folks gathering on a platform to talk about how nice it is, they want it to be their culture too.

It’s more than interest. It’s more than intrigue. It’s monoculture. And it’s emotionally charged because people are passionate about their cultures. Because culture is identity and belonging.

I don’t think a nation can truly experience a monoculture anymore, which has huge implications for our politics and for our societies. But I do think there are across-border monocultures growing, as people experience a more personalised internet that finds and groups people just like them.

How do we navigate that world? A world in which the things that we anll have in common are not geography or local politics, but online cohesion around online cultural moments?

This, I don’t know.

But maybe the answer is to find ways to step outside of our monocultures, physically or virtually.